Nora Isabel Adnams: Life and Labour

‘For the first time in my life I had money problems to be explained to me and just how much money ran one’s life.’ (25)

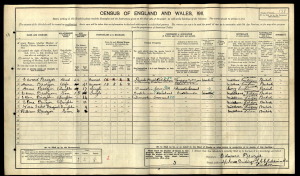

Nora Isabel Adnams’ autobiography provides a fascinating look at life and labour in the 1900’s. Although Nora’s memoir only concentrates on her childhood, she details the hardships of her parents and siblings,and we can unlock more information when we pair this with the 1911 census taken the year Nora returned to her family’s care. Not only do we uncover different jobs of working class lives, but also the indignities and unfairness they had to face.

The beginning of Nora’s memoir, in which her parents are forced to place their children into care, offers a great insight into life and labour of the working class. Nora describes the extreme poverty that her family face, remembering that it resulted in ‘there being only a part of a stale loaf of bread in the house to feed us and no money’ (1). The memoir explains that Nora has six surviving siblings, and that her parents could not afford to feed them, especially after her ‘Father broke his arm, then sprained his wrist’ (1). This information is particularly devastating when paired with the 1911 census (above), as we learn that Nora’s father was an exhibition and house decorator, meaning these injuries would end his career, meaning a severe drop in income for the family.

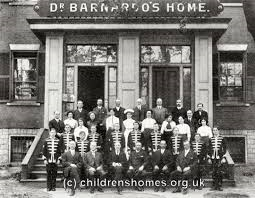

The next steps the family take are dramatic, as Nora’s parents decide to separate in order for their children to be allowed admittance into Dr Barnardo’s homes – ‘Unless we were deserted by at least one parent, I don’t think we could have gone there’ (1). This is indeed the case, as Roy Parker’s Away From Home explains. Barnardo’s received a large amount of requests – ‘for instance, in 1890 Barnardo’s received nearly 6,400 requests for admission to care, but accepted only 1500 – or about a quarter’ (20) – these high demands meant parents would seperate and become more impoverished, to increase the chances of their children being accepted into a home.

Another memory that is particularly focused upon is Nora’s sister, Annie, beginning work ‘in the cook-house, for the laundry people’ (17), which is described as an ‘absolutely soul-destroying’ (17) environment where the girls must iron and wash all day. The conditions are portrayed as strict and exhausting, at which ‘many fainted, but were soon put back in their places again’ (17). It is clear that these images have stuck with our author, and she feels adamant that this work is ‘one of the penalties … of being one of the poor in this world’ (17). This provides a powerful message of the working class being treated inhumanly, and shows how class and position played such a large part in people’s lives in the 1900’s.

Nora goes on to discuss a ceremony in which the laundry workers were thanked by the village with a small amount of money, and how the girls were expected to be ‘grateful’ (18) and Nora remembers vividly ‘the curtsy they had to make’ (18). It is apparent that the work and the money received were in no way proportionate, and Nora comments on ‘the hypocrisy of it, they all considered themselves Christians.’ (18). The idea of the working class being dependent or grateful to those in higher positions, is a great issue for Nora, as she urges her children (and whoever else reads the autobiography) ‘to be generous to the less fortunate, but please don’t be patronising’ (17).

Before Nora returns to her parents, the siblings apply to move to Canada, in an attempt to start a new life. Her parents, however, deny the application and Nora explains that her mother ‘had heard such tales of families taking young girls from home and making proper little slaves of them, and no wages and they never get home again’ (23). Although this may seem like an extreme description, several accounts in Gail H Corbet’s Nation Builders could corrobate Nora’s mother’s description. For example, one former Barnardo’s emigre stated that ‘the man would beat his horse and raise ridges on it’s back, and he did the same to the hired Barnardo’s boy’ (109). Unfortunately, this is not a lone example, with several other similar accounts detailed within Corbet’s work. However, there are also numerous accounts of positive experiences within the book, with the mixed outcomes of childrens’ lives in Canada probably being due to the lack of proper assessment and vetting of Barnardo’s placements in the 1900’s.

Finally, when Nora returns to her parents at the end of the memoir, she notes that ‘For the first time in my life I had money problems to be explained to me and just how much money ran one’s life’ (25). This is an interesting point, as Nora is now exposed to the reality of living independently. Although Nora often felt that she was provided with very little at Barnardo’s, the contrast with home life is very different. Nora, however, see’s the positives of home and states ‘life would be no picnic, but their was LOVE there, which made up for much’ (25).

Laundry Room Image – www.goldonian.org – Web Accessed 20th December

Nora Isabel Adnams’, ‘MY MEMOIRS OF DR. BARNARDO’S HOME, BARKINGSIDE, ESSEX’, , University of Brunel Library, Special Collection: 2:859

Corbett, Gail H. Nation Builders. Canada: Dundurn Press. 1997.

Parker, Roy. Away From Home. London: Barnardos. 1990.

Brazier 1911 Census – – Accessed: 24th November 2014

Barnardos Canadian Headquarters – – Accessed: 29th November 2014

Leave a Reply