Mary Denison (1906 – 1997): Life writing, class and identity.

‘But your nursey years were running to a close, your private school

years, your childhood years. All running to a close, coming to their end’ (70).

As you may have noticed throughout the course of these blog posts, a common theme has been that of class. Mary Denison’s class status shaped the ways in which her childhood developed as it opened doors that other authors on this website did not have. Not only did class influence the path that Mary went on as a child, but it is also influenced how she viewed her own identity. It also crucial to remember that Mary is writing this memoir as an adult who is reflecting back to her childhood. The effect this has is that as readers we are aware that Mary’s perception of her childhood identity may not necessarily mirror the adult identity that she now holds. One aspect of class identity that Mary includes within her memoir is when she first realises that she is wealthier than other people within the parish. Mary recalls a time that she visits a poorer area of the parish with her mother and comments on how she saw ‘poor people, ragged people, out in the streets in the cold and the dark. It was always there, lying at the back of your mind’ (2). This quotation from Mary highlights how class shaped the way in which she produced her life writing. Mary was aware of her privilege and expressed this throughout her writing.

When analysing life writing, Regenia Gagnier says that we must establish which type of working-class autobiography our authors are writing. I believe that Mary’s memoir fits into the category of ‘commemorative narrative. This means that Mary wanted to a capture a moment in time before a change occurred. Gagnier defines the commemorative narrative as having ‘minimal self-consciousness, they preserve memories of a way of life that is changing or has already ceased to be’ (348). I strongly believe that this category can be applied to Mary’s memoir as she wanted to capture her childhood before it began to change as she grew older. I believe that Mary utilises the form of commemorate narrative as a way of bringing back the memoires of her family and home structure.

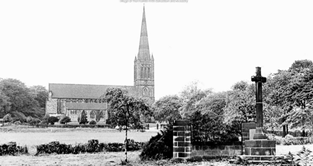

As mentioned, one way that Mary chooses to remember her childhood is through her description of the Vicarage that she grew up in. Throughout the course of her life writing, Mary remembers how the rise in industrialisation began to change the way that the Vicarage looked. Mary says ‘As Leeds stretched outwards, Victorian and Edwardian houses crept into the village, overflowing it in time, and producing a mixture of country village and city suburb’ (3). Mary’s identity is shaped through the Vicarage and its influence on her childhood. In addition to this, Mary reflects on how the Vicarage no longer stands in her adult life. ‘It may as well be called the old Vicarage. Since not a stone of it remains today, nor one memorial of its long life’ (3). This demonstrates how Mary’s memoir fits into the commemorative narrative as Mary attempts to remember the Vicarage before it was knocked down after the War. This highlights how Mary is preserving a memory of what ‘used to be’ (Gagnier,348).

Furthermore, by writing her life story through the commemorative narrative, Mary is able to remember her family in happier times. As we know from researching into Mary’s family, Mary’s mother Ethelred died in 1946. By remembering her family within her memoir Mary is able to look back to a time that her family was alive. A time that she felt sure on her identity. In addition to this, Mary’s brother Michael Denison was killed in action during World War two. In the same way that Mary remembers the Vicarage, she also remembers her family through her life writing. By doing this Mary is making this moment almost picaresque as she is dreaming of a time that she was happy and a time that her family was whole.

As discussed last week, the War played a significant role with how Marys identity was established. The War brought a change to both the place that Mary grew up and to the people that she lived with. The War changed the ways in which the Vicarage was run as the domestic staff began to leave to aid the War effort. As the War began to grow the boundaries of class began to diminish. While the War was taking place, the class divide that had been so prevalent in years prior began to vanish. In addition to this, Mary reflects on how little she knew about the War as a child she says, ‘What did you know about the Great War, as it was called – the background to four of your childhood years?’ (63). As I mentioned last week, Mary lived through two wars and being an adult who lost family in the second World War she reflects on how little she knew. Mary again fits the commemorative genre here as she looks back to a time before the second World War changed her family.

One academic who looked at how class began to change towards the end of the 20th century was Mike Savage. Despite Mary mentioning how class began to change during the War, I have found that her class identity changed in her adult life also. While married to Henry Denison, Mary worked in ‘domestic duties’ which shows that even despite her education she ended up in a role that she had worked so hard to avoid. This also highlights Savage’s point that class has changed over time, even though Mary came from an upper-class family she still found herself in a job that she once deemed for the lower classes. In addition to this, Mike Savage says that ‘This does not mean that class itself is dead. We need to rethink the terms of class’ (104). This can be applied to Mary Denison as it possible that the way that class was labelled when she was a child was different to when she was an adult later in this decade.

Overall, it is evident to see through Mary’s memoir how class affected both her life writing and her identity. Mary was shaped in all aspects of her life by her class status as it opened up doors such as education. It is also clear that class began to change within the 20th century as both the changing in class roles during the War and Mary’s adulthood profession shows. Therefore, I strongly believe that Mary wanted to capture a time when she was sure of her class identity, when she knew what it was to be part of a family and when she had the comfort and the constant stir of the Vicarage. Mary’s life writing dominates the form of commemorative narrative as she wanted to freeze her childhood in a place that she can always look back upon.

Works cited:

Denison, Mary. ‘Church Bells and Tram Cars; a Vicarage Childhood’. Burnett

Archive of Working-Class Autobiographies, University of Brunel Library, Special

Collection.

‘Mary Denison’ in John Burnett, David Vincent and David Mayall (eds) The Autobiography of the Working Class: An Annotated, Critical Bibliography 1790-1945, 3 vols. (Brighton: Harvester, 1984, 1987, 1989): 1:250

Gagnier, Regenia. ‘Subjectivities: A History of Self – Representation in Britain, 1832-1920).1st ed. Oxford University Press. 1991.

Savage, Mike. ‘Social Class in the 21st Century’.1st ed. Penguin Random house. 2015.

Images cited:

Taken from Mary Denison’s title page.

Taken from Ancestry.co.uk

Taken from Ancestry.co.uk.

Leave a Reply