Thomas Jordan (B.1892): Politics, Protest and Class

Thomas Jordan grew up on a colliery in Usworth, County Durham and followed his father down the mines aged 14. Although in his memoir he does not talk about politics, or indeed class in a direct way, he talks about the opinion others had on him because he was a Durham Miner but he also gives us an insight into what it was like to be part of the miner’s strikes.

‘During 1911 there was stoppages of the colliery: putters refusing to go down the pit on the slightest pretext thereby holding to ransom the colliery production – and reducing my earnings.’ (Jordan, 6) The stoppage lasted for the rest of the year and saw a number of miners grow restless at their fate. Thomas explains how the discontent was rising in the colliery, seemingly amongst the younger members of the community, saying that ‘several young men left to join the army’ (Jordan, 6) after this brief period of unrest. Furthermore, the national coal strike which began in March 1912 was the first full stoppage in the coalfield for twenty years and meant that the coal miners were given a chance to enjoy the fresh air of the open fields, but we’re also out of work for a month.

The national coal strike of 1912 came about in a bid to secure a minimum wage for miners in Britain and to replace the structure in place which made it difficult for miners to earn a fair wage for their day’s work. The Durham Miners Association was an anomaly amongst those who wanted to strike throughout the country, having only just agreed on striking at the last minute, and this is due to the fact that their association was mainly a collective with a ‘we’re all in it together’ attitude. (The Journal)

The strike was considered ‘The greatest catastrophe that has threatened the country since the Spanish Armada’ by some (The Times), yet after 37 days the government intervened and put an end to the strike on April 6th by passing The Coal Miners (Minimum Wage) Act 1912.

Prior to this, there had not been a national miners strike since 1894, where miners started the fight demanding a minimum wage, however; this was unsuccessful and, as an outcome, the struggle continued for another 18 years. One of the reasons for their success in 1912 is due to the disruption it caused to the country’s train and shipping schedules and commitments which proved how valuable their work was.

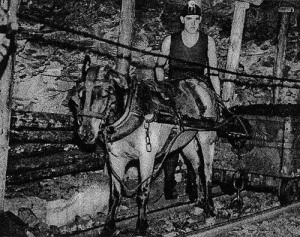

‘In the ensuing year some of them [ponies] became blind and therefore it would still be a dark world to them the next time they emerged from the black pit into those green fields.’ (Jordan, 7)

After the strike, Thomas describes watching the ponies roam free for that month then the heartbreak at some potentially seeing daylight for the last time. It is clear from the memoir that it was during this period Thomas decided he wanted to see more of the world and, like the ponies, he wanted to run free for a bit until he would return and finish the work his father started him on after he served his time during periods of conflict.

Kelly, Mike. ‘Nostalgia: 100th Anniversary of the National miner’s Strike’ The Journal. March 26th, 2012. Web. Accessed December 11th 2013

Thomas, Jordan. Untitled. Burnett Archive of Working Class Autobiography, University of Brunel Library, Special Collection, 1:405

Leave a Reply