Jack Lanigan (1890-1975): Life-Writing, Class & Identity

My life of eighty two years has been a wonderful experience of evolution and revolution, an evolution of having lived from the paraffin lamp to the electric globe, “from the wick to the click,” and a revolution in mind and matter.

Jack Lanigan, ‘Thy Kingdom Did Come’, 83.

This quote comes from a chapter in Jack Lanigan’s memoir titled, ‘What is Life’, which sums up the type of philosophical, even political narrative that Jack Lanigan constructs. Throughout his memoir, Jack Lanigan simply writes about his life, clearly identifying himself as working class given his struggles, poverty and his numerous low paid jobs. However, it seems that the war and other life experiences have changed how Lanigan identifies himself and the world around him. It is from this chapter that his tone begins to change from describing his own life and events and society to questioning these events and society. He questions the war as he states, ‘Have these wars made we human beings any better morally?’ (84). He questions why people have no time given the increasing freedoms in working hours that have been given to them, he asks, ‘Why are so many people bored these days?…Memories of what has been achieved for us to have this freedom is forgotten, the apathy of the masses is really incredible’ (86). The biggest question Lanigan poses is, ‘Where have we gone wrong?’ (86), which portrays a negative image of the society that Lanigan lives in.

Lanigan’s memoir is typical of what Regenia Gagnier calls ‘political or polemical narratives’[1] which she states ‘assert the world changing and the worker’s adequacy to change’ (349). She continues with:

the political narrative is the self-conscious working-class answer to the bourgeois novel…the novel channels all experience into one great conflict, the integration of social process and personal development in time. Like the novel the political autobiography is dedicated to one hero, one odyssey, and one battle. Time is the frame in which the hero is the working class, the odyssey is the quest for political power, and the battle is class warfare. These autobiographers assume the authority to write their own working-class history in order to ensure the subjecthood of working-class autobiography in the future. (351).

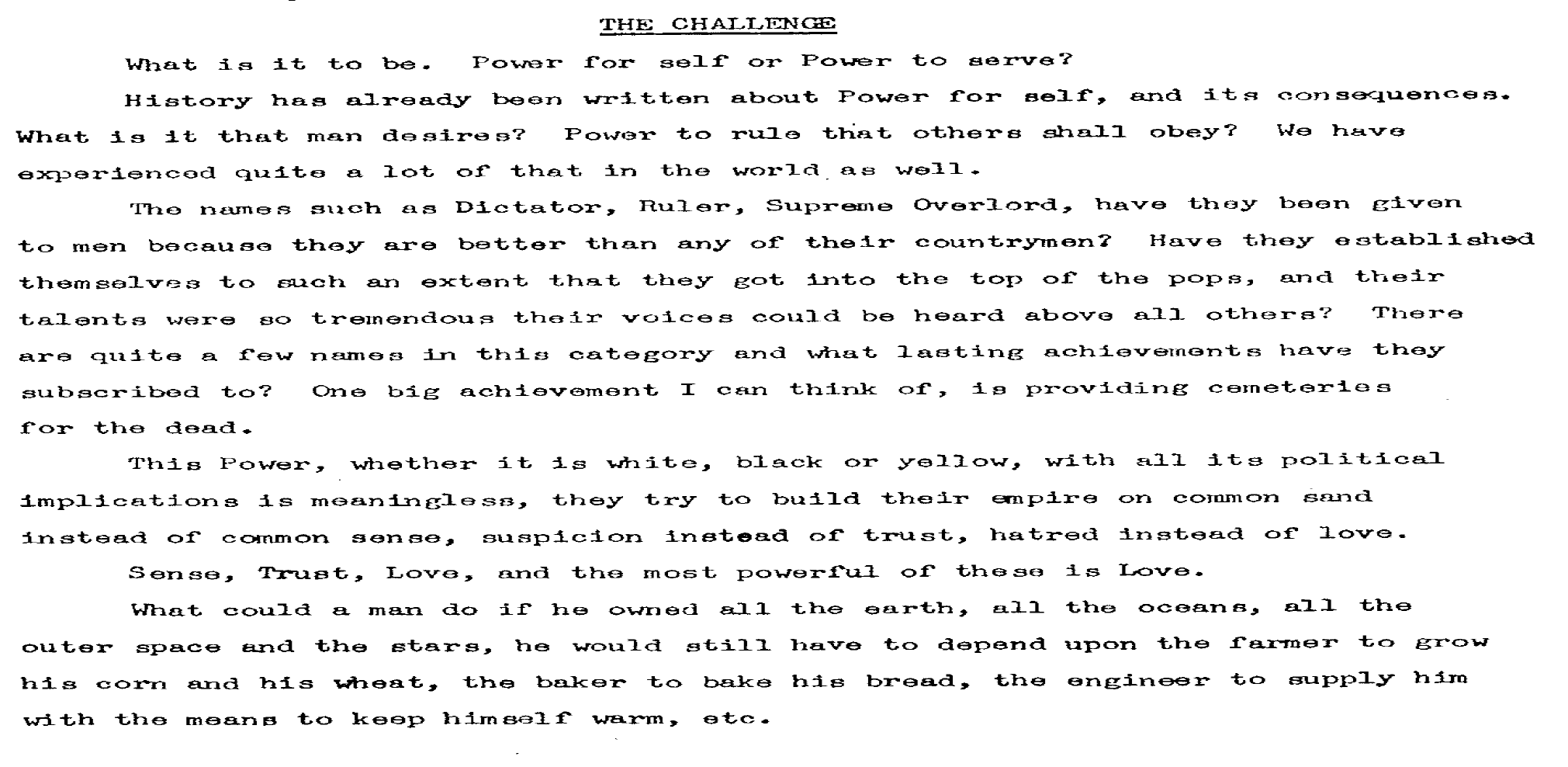

It seems that Jack Lanigan does adopt a political narrative given that, at the centre of his memoir, is the working class as the hero as he shows in the above chapter, ‘The Challenge’, where he states that without the working class, the upper class and the land owners would not exist. As his title suggests, ‘Thy Kingdom Did Come’, Lanigan is explicitly aware of the class system around him, as he refers to hierarchy, power and authority throughout. Lanigan takes politics and class into his own hands, thus, writing his own working-class history ‘in order to ensure the subjecthood of working-class autobiography in the future’ (Gagnier, 351).

However, Jack Lanigan adopts another type of narrative defined by Regenia Gagnier, that being the conversion narrative, which Lanigan explicitly refers to in his appropriately titled chapter, ‘My Conversion’ (63). Gagnier states:

The personal salvation narrative that was primarily a religious form in the sixteenth century was inherited by the nineteenth century in conjunction with other elements of English religion – such as dissidence and non-conformism – and secularized by radical working-class writers. (347)

Despite a decline in conversion narratives in the nineteenth century, Lanigan’s late twentieth century memoir displays more of a sixteenth century narrative rather than the ‘dissidence’ and secularization of the nineteenth century narrative, as he explains how he ‘saw the light’ (63) and became Treasurer of a church. He states:

‘I soon found that through conversion you seem to take a deeper realisation of the things that matter’ (64).

However, the story of his conversion takes up a small proportion of his memoir in comparison to his political views, and therefore Lanigan writes his memoir in a more ‘political or polemical’ narrative form.

Works Cited,

1:421 Lanigan, Jack, ‘Thy Kingdom Did Come’, TS, pp.92 (c.42,000 words). Burnett Collection of Working Class Autobiography, Brunel University Library.

Lanigan, Jack, ‘Thy Kingdom Did Come’, TS, pp.92 (c.42,000 words). Extract in J. Burnett (ed.), Destiny Obscure. Autobiographies of childhood, education and family from the 1820s to the 1920s (Allen Lane, London, 1982), pp.95-9. Brunel University Library.

Gagnier, Regenia. ‘Social Atoms: Working-Class Autobiography, Subjectivity, and Gender.’ Victorian Studies, 30. 3 (1987), 335-363.

Image

1:421 Lanigan, Jack, ‘Thy Kingdom Did Come’, TS, pp.91 (c.42,000 words). Burnett Collection of Working Class Autobiography, Brunel University Library

[1] Regenia Gagnier, ‘Social Atoms: Working-Class Autobiography, Subjectivity, and Gender.’ Victorian Studies, 30. 3 (1987), 345-6. All subsequent references are to this edition and will be cited parenthetically in the text.

Leave a Reply