Thomas Jordan (B.1892): Life and Labour

‘All the hustle and bustle, nowhere peace and quiet: the quest for the black diamond overruled sanity, order and grace. Yet, men and boy did not go insane but rose above the terrible scene and became a particular breed of humans.’ (Jordan, 5)

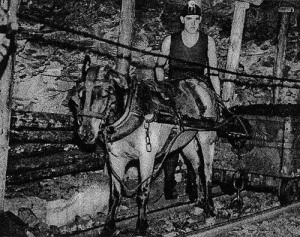

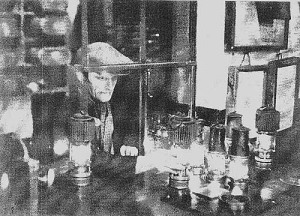

When Thomas Jordan was 20 years old he left his life down the pits and joined the army, longing for those clean barracks and miles of open space after growing up on a colliery all his life. Having left school in 1906, aged 14, he followed his father down the mines and became a traffic boy whose job it was to ensure the doors were opened at the right times to get the coal out and the empty tubs back in. When he was later promoted to a driver it became his duty to care for a horse down the mines and to ensure that things ran smoothly to keep the coal extractions on-target.

For the Jordan family, living and working on the colliery meant that working life was very important; to the family life and to the community as a whole. Thomas expresses great love and admiration for his father, saying ‘I thought he was marvellous’ (Jordan, 10), yet at the same time he is reluctant for his life to mirror his dad’s. He expressed that he was aware from an early age that there was a better life for him, yet all the while he knew he’d return to the area after his time in the army to continue the work down the mines. The dependency upon the community in a colliery means that a certain hierarchy can develop and this is highlighted in his memoirs. He goes into detail about the level of reliance which was placed upon his mother and father throughout their whole lives, seemingly without boundaries, and this brings attention to the relationship between home, work and family spirit in a mining community.

People sometimes had quite a negative opinion on miners in the early 20th century, people from higher classes and from different backgrounds & areas, however; Thomas was never one to force opinions onto others but rather he would diplomatically explain how their work was valuable. Thomas explains how he bumped into a gentleman in a pub who was ‘playing war about the miners being on strike… playing war about the miners saying they were disturbing the country’ (Jordan, 14) however this wasn’t a common occurrence and Thomas states that people who had been in the forces were quite sympathetic to the conditions and the lifestyles, comparing it to life during the war.

‘with the passing of the years I became indifferent to many dangers of the mine: when someone was killed I might become apprehensive for a day or two then the incident was completely forgotten. This training was valuable to me during the first world war when men were yielding their lives on a larger scale.’

For women of this period, ‘in a report on Northumberland, it was noted that unmarried girls worked in the fields, but married girls devoted most of their time to housework.’ (Bourke, 65) This is something which Thomas talks about in his memoir; he states that women didn’t have much of a life and that ‘they were a sad breed of people the lasses were’ (Jordan, 11), though in a mining town it is a close-knit community and it was common for daughters to marry into families from the same area. Thomas makes it clear that it ‘was very seldom anybody in the mining villages went very far in those days’ (Jordan, 12) so community was a key factor in their life.

He was a very proud man who worked hard all his life, overcame illness and always provided for his family. Working in the conditions he did- in the pits and in the army- his health suffered and he thought he would die aged 41 in 1933. This, however, was not the case and he went on to lead ‘an active life in many different jobs with scarcely a day’s absence’ (Jordan, 17) up to retirement in 1963.

Bourke, Joanna. Working-Class Cultures in Britain, 1890-1960: Gender, Class and Ethnicity. London: Routledge, 1994

Thomas, Jordan. Untitled. Burnett Archive of Working Class Autobiography, University of Brunel Library, Special Collection, 1:405

Leave a Reply