On Writing Lives: Impact, Inspiration and Affection

We are delighted to share this blog post by Lesley Hulonce, the first written for our new Guest Blogs on working-class autobiography. Lesley teaches the history of medicine in the College of Human and Health Sciences at Swansea University. Here she writes about how she is using memoirs in the book she is writing on children and the poor laws in England and Wales. To find other posts at Writing Lives on working-class recollections of the workhouse and the poor laws, use our search box. You can read more about Lesley’s research at her wonderful blog . Follow her on twitter @LesleyHulonce and @HistoryMedCHHS or email

We are delighted to share this blog post by Lesley Hulonce, the first written for our new Guest Blogs on working-class autobiography. Lesley teaches the history of medicine in the College of Human and Health Sciences at Swansea University. Here she writes about how she is using memoirs in the book she is writing on children and the poor laws in England and Wales. To find other posts at Writing Lives on working-class recollections of the workhouse and the poor laws, use our search box. You can read more about Lesley’s research at her wonderful blog . Follow her on twitter @LesleyHulonce and @HistoryMedCHHS or email

***

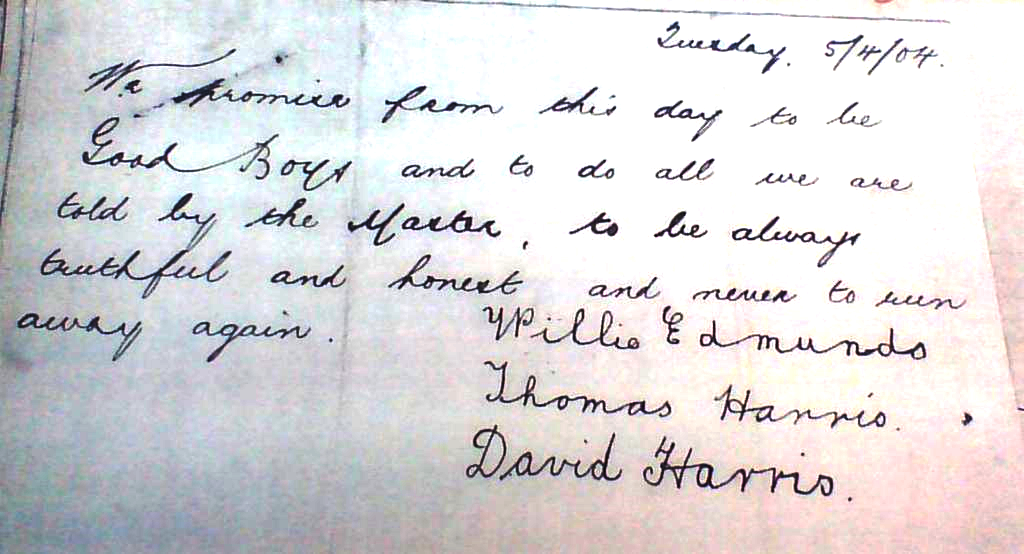

On Tuesday 5th April 1904 three boys who lived in Swansea Poor Law Union’s cottage homes signed a promise to be ‘Good Boys and do all we are told by the Master, to always be truthful and honest and never to run away again’.[1] This document (below), while written by an adult, was signed by the three boys themselves – Willie Edmunds, Thomas Harris and David Harris. Although their signatures are very neat the various embellishments to their letters (especially Willie’s rendering of ‘W’) demonstrate the boys’ individuality and has brought tears to my eyes on many occasions.

When I started researching children and the poor laws I remember my excitement when I found this slip of paper pinned within the leaves of a ledger. It was the only document that I know to have been touched by ‘my’ children. We can glean some useful information from it too; the boys had absconded from the institution but had returned. Whether they came back of their own accord or were found by the police is not known. Neither is why they ran away – were they unhappy or were they on an adventure? The master had tried to appeal to the boys’ honour, and I can imagine it was a solemn occasion, maybe with witnesses present, when he asked the boys to sign this pledge. And of course it shows that neat handwriting was taught in the school the boys attended. But, wouldn’t it be amazing if Willie or Tom or David had written about this incident themselves?

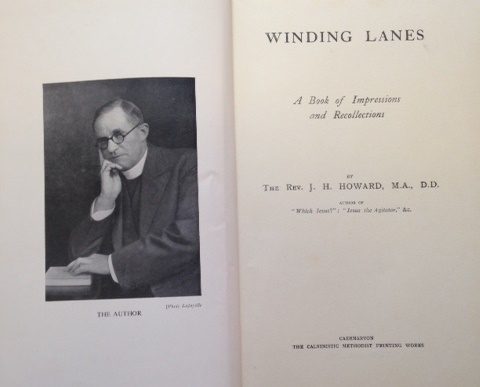

As far as I know these boys did not leave any written words behind, but one former cottage homes lad did. I was writing in Swansea Central Library when the wonderful local studies librarian showed me a book called Winding Lanes (1938) by James Howard who had lived in the cottage homes a child.[2] This autobiography changed my thinking about research into children’s lives and also caused me to reformulate some of my arguments. I was fascinated to see that James Howard appeared to be very bitter about corporal punishment in the cottage homes but seemed to accept it in the local elementary school. I was also intrigued to see that he didn’t remember the wife of the superintendent, but instead referred to him as an ‘old bachelor’ although Mrs Grossmith had run the homes single-handed for a while after her husband’s death.[3] How children perceive their world can be very revealing, and I realised that James probably knew Mrs Grossmith as ‘Matron’ rather than the wife of a rather crusty-sounding ‘old warrior’. As Richard Coe argues ‘it is often in the very wrongness of the unverifiable recollection that its significance lies’.[4]

Establishing these connections between life writing and other primary source material offers enhanced understanding but also generates more questioning. When James lived in the cottage homes the children were given numerous treats and outings, especially in the months and at . James did not mention any of these in this chapter of his memoir, but focussed on punishments, loneliness and hunger. His memories of school were completely different. He called it a ‘joyous’ time and related with no little relish how the boys took part in at least one organised fight a week, generally on Fridays after school. One battle lasted for three evenings in a row; ‘night and mutual exhaustion were the only interruptions possible’.[5] Although this reveals that the children could enjoy free time after the school day had ended (and quite possibly the reason behind some of the punishments) the cottage homes were never ‘home’ to James and his discontent is evident on every page.

I remember a comment on Twitter some time ago saying how disappointing it was when a book purporting to be about children’s lives was instead full of government policies. This observation stays in the forefront of my mind while I’m writing my book about children and the poor laws in England in Wales. I am using James’s story as well as many others ranging from famous former child paupers, such as Charlie Chaplin’s and Henry Morton Stanley’s memoirs, to unknown writers such as Edward Balne from the Burnett Collection; Joseph Bell whose story is in the Bedfordshire Archives & Records Service; and the wonderfully named Lucy Luck who features in Useful Toil by John Burnett.[6] I am inspired by Jane Humphries who consulted 600 working-class autobiographies for her wonderful book Childhood and Child Labour in the British Industrial Revolution, and the cache of information in her bibliography.[7] Similarly, the students’ posts at Writing Lives have been so helpful and endlessly fascinating, and are the result of the dedication and innovative teaching methods of Helen Rogers who never fails to inspire me. Hopefully more of the amazing Burnett Archive used by the students for Writing Lives will be digitized in the future and made available so that more of this precious archive can be read by historians of working-class life worldwide.[8]

[1] West Glamorgan Archive Service (WGAS), U/S 85, letter in Cockett Cottage Homes Visiting Committee Report, 5 April 1904.

[2] J. H. Howard, Winding Lanes: A Book of Impressions and Recollections (Caernarvon: Calvinistic Methodist Works, 1938).

[3] WGAS, U/S 1/18, Guardians’ Minutes, 28 May 1885.

[4] Richard N. Coe, ‘When the Grass was Taller: Autobiography and the Experience of Childhood (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 1984), 2.

[5] Howard, Winding Lanes, 23, 25-26.

[6] John Burnett, ed., Useful Toil: Autobiographies of Working People from the 1820s to the 1920s (London: Routledge,1994), 53-63.

[7] Jane Humphries, Childhood and Child Labour in the British Industrial Revolution, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

[8] The Archive is deposited at Brunel University and some of the collection is available online at

Leave a Reply