Charles Whiten Sanderson (1906-1990): Fun and Festivities (Part One).

“All would gather round the organ on occasions and sing until the rafters rang” (31)

Unlike other working-class men such as Cecil George Harwood, who discusses life and labour to great extent in his memoir ‘Down Memory Lane’, Charles uses his memoir to reminisce about fun and festivities that he experienced as a child. Fun and festivities constitute a large and sentimental portion of his writing when reminiscing about childhood in Sutton-in-Ashfield!

Charles begins by reminiscing about the first holiday of the school year. ‘I believe our first half day holiday of the school year was Ash Wednesday…the only real significance it had for us was that we had a free afternoon’ (24). Playfully admitting that Ash Wednesday was less about the religion and more about the half day in school, we are given insight into the types of holidays children such as Charles received in education. ‘The great day was the preceding one, Shrove Tuesday, better known as, “Pancake Day” …pancakes, and nothing but pancakes for dinner. During the morning at school, there was much speculation as to how many we could each put away’ (24). Of course, it wouldn’t be Charles’s memoir without a light-hearted recount of how other mischievous children like himself celebrated Shrove Tuesday! From half days to pancake eating competitions between friends, recounting the type of festivals Charles experiences with his school, family and other children in the town, we can explore further how children grew up in early 1900s with aspects such as religion and the rapport in the community as they grew up in.

When reflecting on Easter, Charles focuses more on the food that came from the holiday. ‘The mint humbug deserves special mention. It was a huge piece of mint flavoured boiled sweet almost as big as an apple…two alternatives of reducing it to a manageable size; one to break it…the other, to lick it.’ (24). Fondly remembering the dilemma of eating humbugs just simply resonates the cheerful childhood Charles had. ‘The annual penny chocolate Easter Egg’ (24) evoked my interest when studying the childhood Charles had and how the value of money has changed between early 1990s to 2018. Charles also discusses another change in society from his childhood to modern Britain: ‘No-one today would believe the abject poverty of some homes of the time’ (25), reflecting on poverty amidst the fun and festivities, it deepens the understanding of working-class life in Britain.

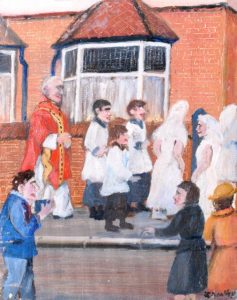

Another festival Charles focuses on is ‘Whit Sunday’ (26), also known as Whitsuntide, the eighth Sunday after Easter. Mary Hollinrake’s memoir ‘Lancashire Lass’ also mentions both Easter and Whitsuntide. According to Charles, ‘Every kid in town had to have his annual rigout…it was a matter of parental pride…This clothes phenomenon made its debut on the Sunday’ (26). This ‘parental pride’ can be interpreted as a symbol of class and potentially an indication into how much money some families earned. ‘The custom was to go off and show yourself off to aunts, uncles and grandmas, in the hope that they would give you a copper as a compliment for your smart appearance, though my own father always strictly forbade us to take such gratuities’ (26).

By Charles describing the festival as children being showed off, it reiterates the underlying issue of class in the 1900s. This is explored by Joanna Bourke[1] in Working-Class Cultures in Britain, where she discusses the correlation between class and festivals: ‘Clothes were another indicator…Kenneth Leech, agreed that an individual’s ‘class’ was a matter of distinctions of in material culture… ‘The poor children…whose parents could not afford new clothes at Whitsun, had no part in the processions’’ (3). Quoting Kenneth Leech[2] in her argument, Bourke discusses the festival of Whitsuntide. By analysing this and Charles’ description of his family life and their ability to buy him new clothes for Whit Sunday, I am assured that Charles and his family were a stable working-class family in comparison to others.

A significant festival in Charles’s memoir is Christmas. ‘The next great festival was Christmas…that magical time for children which means carols and Santa Clause’ (40-44), from being told stories to the deeper meaning, ‘We were told Christmas stories and taught the meaning of Christmas…feverish excitement and breath-taking anticipation’ (44). This fun and nostalgic memory for Charles and his family radiates happiness, including the gifts he and his siblings received in their stockings: ‘We would find an orange, an apple, a bag of sweets (these were an unusual treat), perhaps a drawing book or a game of ‘Snakes and Ladders’ but one small consolation would be a lovely shiny bright new penny’ (45). Charles portrays a loving and sentimental depiction of Christmas in the Sanderson household.

‘Is there anything quite like the old English Christmas as we knew it? I can only recall through the eyes of a child, but to me it was sheer magic…We would be allowed to stay up until midnight on new year’s eve, to hear the church bells ring out the old and ring in the new. Thus passed another year’. (46).

Bibliography.

Sanderson, Charles Whiten. ‘Half a Lifetime in the 20th Century’ Burnett Archive of Working Class Autobiographies. University of Brunel Library. Special Collections. 688.

688 SANDERSON, Charles Whiten, ‘Half a Lifetime in the 20th Century: A Book of Memoirs’, TS, pp.115 (c.78,000 words). Extracts published in Mansfield and North Nottinghamshire Chronicle Advertiser (Chad), 13 March – 31 July 1980 (Sutton-in-Ashfield Library). Brunel University Library.

[1] Bourke, Joanna. Working-Class Cultures in Britain 1890-1960. London: Routledge, 1994.

Harwood, Cecil. ‘Down Memory Lane.’ Burnett Archive of Working Class Autobiographies. University of Brunel Library. Special Collections. 1:309.

Smith, Lucy. ‘Cecil George Harwood (1894 – 1983): Life and Labour I’ 6 April 2018. Writing Lives. Web Accessed 10 April 2018.

Hollinrake, Mary. ‘Lancashire Lass’. Burnett Archive of Working Class Autobiography, University of Brunel Library, Special Collection, 2:413. Extract in John Burnett, David Vincent and David Mayall (eds) The Autobiography of the Working Class: An Annotated, Critical Bibliography 1790-1945, 3 vols. (Brighton: Harvester, 1984, 1987, 1989): 2:413.

Shea, Holly. ‘Mary Hollinrake (b. 1912): Fun and Festivities’. 21 January 2016. Writing Lives. Web Accessed 10 April 2018.

[2] Leech, Kenneth. Struggle in Babylon. London, 1988, 1-2.

Images.

‘Corpus Christi Whit Sunday, 1984’ By James Bentley. Flintshire Museums Service.

‘Tossing the Pancake’ by George Cruikshank, 1837.

‘Old Father Christmas’ by William Ewart Lockhart. Hunterian Art Gallery, University of Glasgow.

Leave a Reply