Florence Powell – Education and Schooling

Education and Schooling

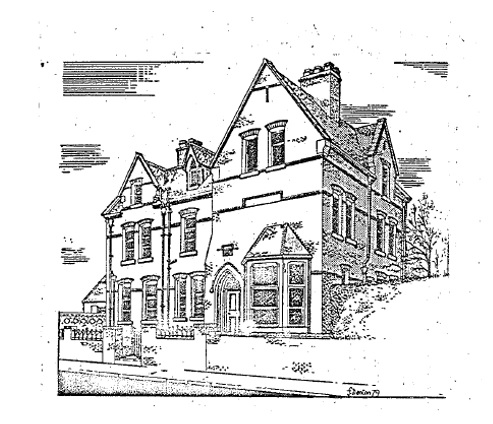

Florence Powell’s experience of education and schooling may have been somewhat limited, however the orphanage she attended describes itself as:

‘A training home for orphan girls. The design of the charity is to provide maintenance, clothing and instruction for orphan girls, with a view of fitting them for domestic service, to train them in household work and educate such children in habits of frugality, industry, within the principle of the Church of England’. (p.1)

Powell’s experiences of education are a major theme of the memoir itself. Her reflections are useful to readers, as she describes the mixed emotions and events throughout her education at the orphanage through a natural stream of consciousness, depicting the good and the bad memories openly to readers. As summarised by J.S Hurt (1979):

‘Much of the history of education has been written from the top, from the perspective of those who ran and provided the schools, be they civil servants or members of the religious societies that promoted the cause of popular education. Little has been written from the viewpoint of those who were recipients of this semi-charitable endeavour, the parents who paid the weekly school-pence and the children who sat in the schoolrooms of nineteenth-century England’ (p.25)

With Hurt’s point in mind, it is especially useful that Powell so vividly documents education throughout her memoir, as her memoir is a significant contribution towards a working-class representation of schooling.

Education vs housework

Powell’s reflection on schooling within the orphanage also provides readers with some interesting insight into gender roles and expectations during this time period. Powell bluntly states: ‘I loved the school, not because it was a place of learning, but because it provided a rest from household chores’. This suggests that for Powell, education was an enjoyable experience in some ways, and viewed as a form of escapism from household chores such as scrubbing the floor. However, she also indicates that the escape from her everyday routine could be quickly broken, describing: ‘Sometimes even in the middle of a lesson Miss Simmons would come in to take someone to task. One of the most familiar complaints was that the hall floor had not been scrubbed to her liking’. Powell’s vivid memory of this reaffirms to readers the anxiety felt by Powell towards missing out on her education, while it also gives readers insight into exactly what the priorities of young girls and women were expected to be.

The importance placed on housework within the orphanage clearly outweighed the importance of gaining an education as the staff had no problem interrupting a lesson, despite the fact it annoyed the teacher. Powell also goes on to tell readers that her teacher, Miss Harrison ‘did her best to try and get better conditions for the girls, and did not agree with the others being so strict with us’, yet Powell quickly elaborates: ‘I suppose that being a charity home, she was fighting a losing battle’ (p.14). Powell’s use of the phrase ‘fighting a losing battle’ depicts the pessimism she evidently felt towards her education throughout her time at the orphanage. It’s clear that no matter how much the girls may have been willing to learn, factors such as social class and gender were always standing in the way of their progress to some extent. The girls themselves were in no place to argue with members of staff, and due to their circumstances, few people had the authority to improve their experience.

Although education was interrupted by chores, it is clear that there had been some progress made throughout the nineteenth century in regards to schooling. As argued by Eric Hopkins (1994, p.1), the end of the nineteenth century saw some significant changes:

‘The nature of childhood was better understood, both in respect of relationships with the adult world, and in its influence on learning processes in school’ (p.1)

The uniform

Powell’s also descriptively recalls the uniform the girls at the orphanage were expected to wear, sharing: ‘The outdoor uniform was quite attractive – We all liked it – the winter coat and hat was made of velour, warm and comfortable’, yet she wasn’t so fond of the indoor uniform, explaining: ‘our indoor uniform was not so nice – rather old fashioned black serge dresses worn with white cotton pinafores and fastened with white tapes at the back’. (p.2) Powell’s juxtaposing of each uniform is effective as the use of positive language such as ‘warm and comfortable’ helps readers to relate more to Powell’s memories and imagine the scenes she is describing more clearly.

However, the description of the indoor uniform reminds readers of the harsh rules and regulations of education, reaffirmed by Powell as she writes in a light-hearted, humorous tone, ‘Boots were worn in the week and shoes on a Sunday. Woe betide anyone who did not have them shining bright!’ The variety of feelings Powell expresses gives readers an enjoyable and realistic representation of education.

Works cited:

Hopkins, Eric (1994) ‘Working-Class Children in Nineteenth-Century England’ Manchester University Press

Hurt, J.S, (1979) ‘Elementry Schooling and the Working Classes, 1860-1914’ Routledge & Kegan Paul p.25

Powell, Florence, ‘An Orphanage in the Thirties’, duplicated pamphlet, Illustrated. Brunel University Library

Leave a Reply