George Gregory (b. 1888): Education and Schooling.

Despite being born to illiterate parents in a village which existed almost solely to house coal miners, George had an insatiable appetite for knowledge – demonstrated in his endless quest for further education. His desire for knowledge started very early, when as a child he was ‘allowed… to attend a primitive Methodist Sunday school’ (9). George’s use of the word allowed implies that he wanted to go of his own accord, rather than being forced to by his parents or the government. George notes explicitly how he ‘liked going to school, and took an interest in lessons’ (36) which I think is surprising giving his circumstances and position in society – factors that would normally limit a child’s potential appreciation for formal education.

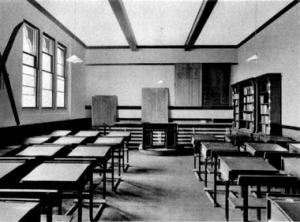

At the age of 16, four years after leaving compulsory schooling, George made the decision to return for evening classes. This is hugely important and really shows the longing he had for some kind of further knowledge, as the extra schooling ‘cost a small fee’ (63), and at this point in his life he wasn’t exactly wealthy. He also writes how he had to ‘walk more than a mile to attend the class, and that after a day’s hard manual work in the pit’ (63).

George excelled in his evening classes, regardless of the obstacles in his way, and was awarded a book for ‘good conduct and progress’ (63). He writes, charmingly, that he ‘treasured it until recently even after a thousand others had gone from [his] collection’ (63), really highlighting his sentimentality towards that period of his life.

In the autumn of 1906, George once again returns to his school for evening classes, but this time with a focus on mining. I think it is interesting to see how his background shaped his interests so blatantly. He was very engaged with practical lessons and was eager to understand more about the ground beneath his feet, where he, and his father before him, worked. George relished his mining classes and was proud of his advancement and the career that lay ahead of him, shown as he tells us ‘I… had a feeling that my progress was good for I was able to tackle papers that were set for the second class exam’ (66).

Arguably as important as institutionalised schooling to George, however, was general, self-motivated education. He often writes about his thirst for books and the growing collection he was amassing, at one point saying he ‘looked at it with a feeling of pride and pleasure’ (65). George applied what he learned in his classes dynamically to the world around him and found great joy in recognising things he had recently learned about in nature. For example he describes how he had an interest in fossils and ‘often went to a quarry in search of them’ (65). This is the kind of drive and enthusiasm that I think set George on his successful path in life.

Researching and exploring George’s relationship with education and schooling was massively gratifying for me. It not only brought me closer to him as a subject, but also gave me perspective on the very idea of self-improvement. If George, in the harsher environment of the late 19th and early 20th century, managed to juggle a full time manual labour job beneath the earth with rigorous studying and mental development, surely I can manage my own, comparatively relaxed life.

Gregory, George, ‘Untitled’, Burnett Archive of Working Class Autobiography, University of Brunel Library, Special Collection, 1:283.

Leave a Reply