Alfred Ireson (b. 1856): Life and Labour – Part One

Considering the sheer wealth of memory that Alf writes about his times of work, it is only natural that it should be covered over two posts; both hopefully showing the most inspiring and intesting elements of Alf’s memoir yet. This first post will outline the earliest years of his extensively rich working life, which was encompassed by an array of manual humble work in the country, fuelled by a tenacious spirit for life experience.

It seems commonplace to perceive working-class individuals at the turn of the century as having hugely laborious lives; work hours long, with little financial incentives, many families barely earning enough money to survive. However, Alf’s working life, was not the norm, nor was it a tremendous struggle like so many others in the working-classes. ‘While most working-class individuals still retained the outlook and thought patterns imposed by their Victorian mentors…Docilely they accepted a steady decline in living standards and went on wishing for nothing more than to be “respectful and respected”’ (Roberts, 1971, 31) Alf sought much more than to remain ‘docile’.

His work corresponds with his need for freedom and independence; by finding work that did not tie him to a particular location, his life revolving around his next conquest, he once again displays his optimistic viewpoint that ‘the grass is always greener’. Instead of ‘working-to-live’, like many other working-classes, it seems Alf ‘lived-to-work’. Much of his identity and self-created purpose stemmed from the successes of his working life; with the majority of his memoir dedicated to the stories he acquired through his years of travel and labour.

My first job was on a farm…to scare crows from the newly growing corn’ (25) he writes, where he states that he had to be ‘up with the crows’ (25) and did not leave for him well until they had resided to their nests again. This small description is nestled under the minor subtitle ‘Ambition to work’ (25), and provides the first impression of Alf’s honest thirst for possible financial and domestic independence away from his comfortable family life. Contrary to other working-class children growing up in the country, Alf’s childhood was not blighted by forced child labour; instead ‘labour’ was used as a keen opportunity to define his independence and clarified his sense of self-worth from a young age. The Factory Act of 1850 which established the standing working day and The Education Act (Forster’s Act) passed in 1870, (which set up school boards to provide education for 511 year olds), ensured that Alf’s childhood was never completely devastated by the possibility of long working hours and little or no opportunity for education or even fun. Times were starting to change.

Nonetheless, Alf wanted to work; he had ambitions, and a vocabulary that did not contain ‘I can’t’. He later describes his pocket money, which he received from making nets, and was his ‘keenest interest. I think for a lad my energy for work was above the normal’ (26) and there was no employer in town that would refuse him a trial. His honesty in explaining his early desire for financial stability and a more than ample work ethic brands Alf as a more than capable ‘bread-winner’ and a credit to any future profession he undertook.

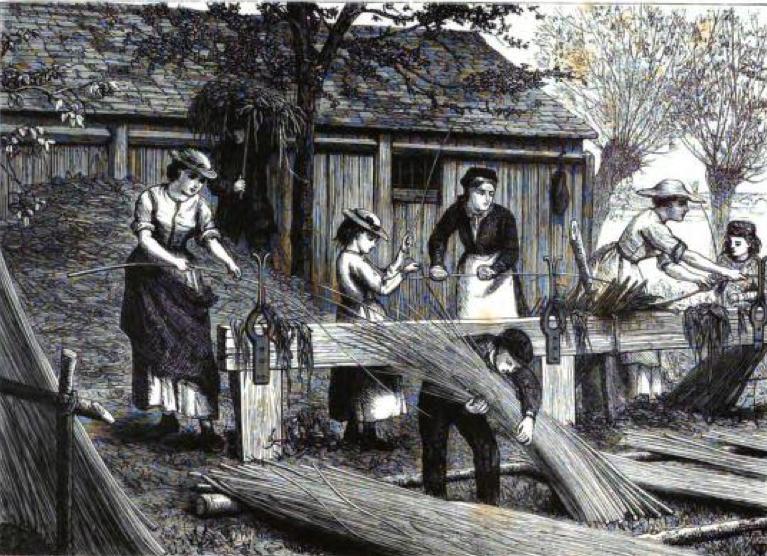

Early years of work gained Alf the most extensive set of skills that any man could ask for. A Farmer’s boy who harvested and hay-made, a Butcher’s boy who sharpened knives and assisted the slaughters, a printer and book-binder, bootmaker, carpenter, Iron foundry worker and even an osier peeler…the yearning to learn and experience drove Alf from work to work and instilled the work ethic that his Mother was no doubt elated by. As Gagnier believes many working-class autobiographers ‘write from a place where time is not correlated to money’ (1987, 349), it may seem certain that Alf’s incessant changes of work were not in search of a better pay check, but for a way to make the world around him better…

For the second part of Alf’s Life and Labour post, please click here

Works Cited:

Ireson, Alfred. ‘Reminiscences’, TS, pp.175 (c.35,000 words). Extract in J. Burnett (ed.), Destiny Obscure. Autobiographies of childhood, education and family from the 1820s to the 1920s (Allen Lane, London, 1982), pp.82-8. Brunel University Library.

Gagnier, Regenia. 30.3 (1987): 335-363

Roberts, Robert. The Classic Slum: Salford Life in the First Quarter of the Century. UK: Penguin Books, 1971

Images Cited:

Peterborough Images: Whittlesey Workhouse. Web. Accessed 3rd January 2016. http://www.peterboroughimages.co.uk/blog/category/villages/whittlesey/page/2/

The Victorian Web: Osier Peeling — rural work for men, women, and children. Web. Accessed 3rd January 2016. http://www.victorianweb.org/history/work/22c.html. Taken from: Robertson, H. R. Life on the Upper Thames. London: Virtue, Spalding, & Co., 1875.Internet Archive digitized from a copy in the University of Toronto Library.

Leave a Reply